By that, I mean that not only should we understand what actually happens in the brain to create pathways of learning, but also how we, as individuals, learn. To do that we need to understand how we think and our attitude towards learning and the learning environment we are in. We need to be mindful of the habits that help effective learning or the beliefs that hinder effective learning. We need to be mindful of the roles attributes such as working memory play. We need to be especially mindful of what motivates us to achieve academically (or in any other area of our lives) and of what demotivates us so that we give up on our attempts to learn.

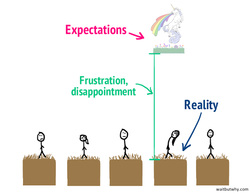

Perhaps the first place to start is to understand how you view learning and your beliefs about how well you have been able to do it so far. The way you think about how ‘smart’ you are is intricately linked to your self-esteem, so it is crucial to understand how you view learning. Is it just a means to an end - something you have to endure for thirteen-odd years before you can finally do your own thing? Do you feel that other people seem to have gotten it right but you haven’t? Do you believe that the ability to learn and be academically successful is a fixed ability and not amount of hard work will change it? Perhaps you are in high school and are finding it a lot harder to keep up now than when you were in primary school? Do you associate the ability to learn with being ‘smart’ while any areas of difficulty means you are ‘dumb’? Carol Dweck believes your mindset towards learning is key. She believes there are two different kinds of mindsets – one that is fixed and believes that all your qualities are set and unchangeable; the other believes you are able to grow and develop your basic abilities through effort, hard work and learning from experience (Dweck, 2006). Which one are you? Dweck advocates that ‘…the belief that cherished qualities can be developed creates a passion for learning’. But change is hard. We often cling to a fixed mindset because those beliefs have served a purpose in our lives – they have defined who and what we are. They have told us how to act in order to win acceptance. It can be daunting to undo a lot of what you have come to believe. But the journey is worth it. The more mindful you are about what works / does not work for you, the better you will be at developing a work ethic that enables you to creatively tackle any problem you may face as well as study habits that WORK.

But your mindset is only part of the bigger picture…

A very important aspect of effective learning is your working memory. Working memory is a better indicator of academic success than IQ (Alloway, 2011)). This is the third and lesser known aspect of our memory system. I am sure you have all heard about short term and long term memory, and will have some sort of understanding as to their respective roles in learning. Short term memory is learning’s front door. We receive information through our five senses. Short term memory decides in split seconds what to keep and file away in long term memory, what to use right now or what to discard. For example, without going back and reading from the start, I can guarantee you will not be able to remember EVERY word written so far! But… you will remember the gist of what has been said. Long term memory is our storage facility - the warehouse of all the things we know, have experienced and understand. Working memory is where the two come together. It is here that every detail of the task has to be held, information manipulated, and a product produced. This product could be a piece of writing, a verbal answer to a question, a decision on a course of action or even referencing what you already know about this subject to what you are reading right now. I like to think of it as an imaginary desk where everything needed to complete the task is placed for use. We are all born with varying sizes of ‘desk’. So even though you may find you struggle with aspects of working memory, you CAN learn strategies to help you cope. For example, research has shown that regular meditation or mindfulness training helps the brain focus better, and can even improve your ability to pay attention to task at hand. (van Vugt and Jha, 2011;).

The report indicates that the quality of information you take in improves, and the time you take to think about it and respond to it is reduced. Another example is hand writing. Writing is probably the most demanding activity you can do as a human as far as working memory is concerned, especially for younger children. There is a great deal involved that you take for granted. The brain has to remember how to hold the pen, how to recognise the shape and sound of every letter and how groups of letters make a word, how those words need to be spaced and written so that they make sense. It has to remember how to punctuate, how to use figures of speech, how to use paragraphs. All the while it has to remember the bigger picture of the story or sentence, how to word the paragraph so that it reflects your arguments, and so it goes on… all this is held in your working memory. The desk rapidly becomes full or even overloaded. The first things to fall off are things such as spelling and punctuation. You might omit words as you write. You might forget what you have seen when copying from the board. When reading, you might forget what you read at the top of the page when you get to the bottom. Even the phrase ‘I work so hard but cannot seem to get the results…’ could indicate a poor working memory. I need to emphasise here that none of the above-mentioned difficulties alone can indicate a poor working memory – they could also be indicative of other learning difficulties. But if you feel you do not have any other serious problems, it is a place to start looking for strategies to help you work smarter rather than harder.

Motivation, or lack thereof, can also affect the quality of your learning. Not only do you need to be aware of what encourages you to learn (reward, fear of failing), but you need to be mindful of the things that stop you from achieving your potential (criticism, fear of failure, beliefs about your intelligence).

Being mindful of how you think and learn is the beginning. Learning strategies, trying them out and applying them to your daily studies are the next steps. Success (no matter how large or small) will create positive experiences for you that will result in feelings of confidence, and power. After all, knowledge is for the brain and experience is for the body. Together they will change your behaviour and the actions will become who you are.

Learning is a multi-facetted activity. Many genetically inherited aspects can affect it to varying degrees, but there is a lot you can do to make learning a more positive experience for yourself. Being mindful of how it works and what works for you are wonderful skills to have. Mindfulness training not only helps in this particular area, but the results will be felt in all aspects of your life. These skills will ensure you become a life-long learner. What a journey to have ahead of you!

In future blogs, I would like to take a more in-depth look at some of the most important aspects of effective learning. I would like to share some of my experiences with you, and offer some strategies you might like to try.

Yours in lifelong learning

Caroline Rimmer

References

Dweck, Carol (2006). Mindset: how you can fulfil your potential. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd.

Van Vugt, Marieke K and Jha, Amishi, P (2011). Investigating the impact of mindfulness meditation training on working memory: a mathematical modelling approach. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience (2011) 11: 344 – 353

Alloway, T.A. (2011). Improving Working Memory – Supporting Students’ Learning. London: SAGE

RSS Feed

RSS Feed